Contact : +254 725 877 146

The Living Legacy of Trees: How Trees Shaped Our Place Names

Trees are the silent architects of life. They breathe for us, feed us, clothe us, heal us, and even house us. From the fruit that nourishes our bodies to the oxygen that sustains our lungs, from the timber that builds our homes to the roots that hold our soil together, a tree has given humankind almost everything it has ever needed.

In Africa, the tree is far more than a natural resource; it is a symbol of life, resilience, and community. Beneath their wide canopies, people met to settle disputes, pray for rain, bless harvests, and crown elders. The shade of a tree was the first council chamber, the first classroom, and sometimes, the first church. Many African societies regarded certain trees as sacred, believing spirits or ancestors resided in them.

But beyond their ecological and spiritual roles, trees also left an indelible mark on our geography. Across Kenya, many towns and villages derive their names from the trees that once defined their landscapes. These names are living reminders of our deep connection with the natural world, even in places where the original trees have long disappeared.

Take Kamiti, for example. The name is believed to come from the Kamiti tree, sometimes called the Thika palm (Filicium decipiens), which once grew along the Kamiti River. The area was known for its swampy forests, and the tree’s abundance made it a natural reference point for early settlers.

In Nairobi’s leafy suburbs, Kileleshwa bears the memory of the Leleshwa tree (Tarchonanthus camphoratus), a hardy, aromatic shrub revered by the Maasai for its cleansing scent and resilience. The Kikuyu called it Muriricua, and from the blend of languages, the name Kileleshwa emerged. Ironically, today, the area is covered in concrete towers, yet its name still whispers of the shrubs that once perfumed the breeze.

A few kilometres away lies Muthaiga, named after the Muthiga tree (Warburgia ugandensis), also known as East African greenheart tree. This tree is valued in traditional medicine for its bitter bark used to treat fevers, coughs, and stomach ailments. In the past, elders gathered under the Muthiga tree for discussions, its presence symbolized health, wisdom, and authority.

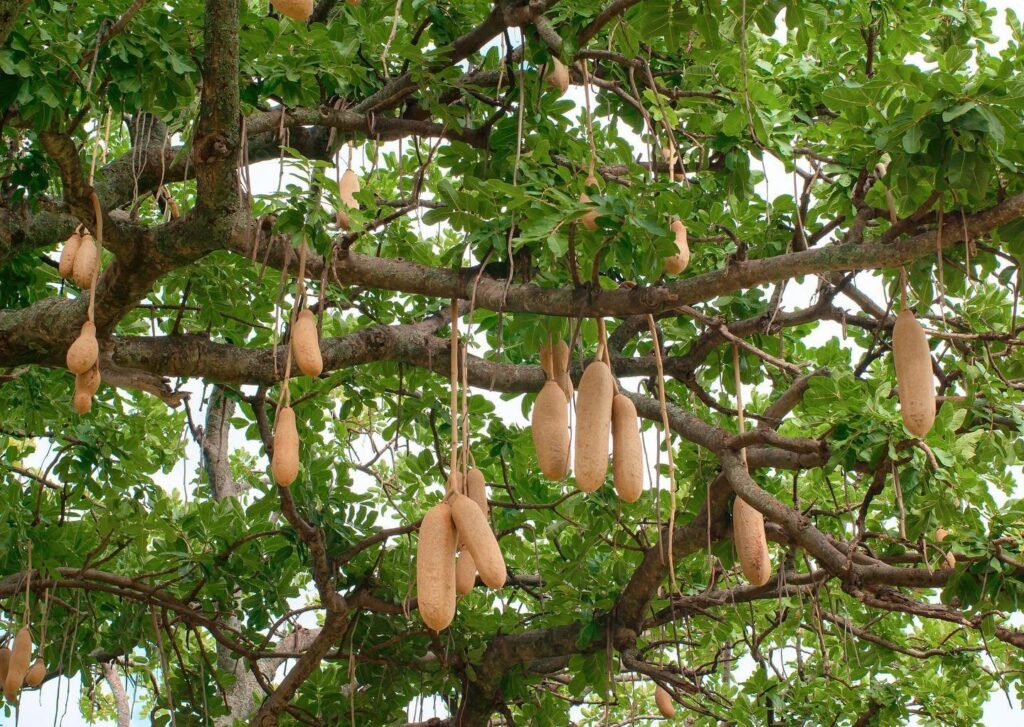

Further north, the bustling town of Karatina carries its own leafy history. Legend has it that early traders met under a Muratina tree (Kigelia africana), famous for its sausage-shaped fruits used to make traditional brew. The market that grew around it became known as Karatina, a name that outlived both the tree and the early traders.

In the highlands of Kirinyaga, Kagumo town derives its name from Mugumo, the sacred fig tree (Ficus sycomorus). The Mugumo tree is deeply spiritual among the Kikuyu, believed to be a meeting point between the people and Mwene Nyaga, the creator. No one dared cut it down; to do so was to invite a curse. The name Kagumo, meaning “place of the small mugumo tree,” preserves that reverence in the language of the land.

In Embu County, Mukuuri also traces its name to a mighty fig tree that once towered over the settlement. Locals called it Mûkûûrî, meaning “the large one,” and gathered under its branches for community gatherings.

Even along the coast, tree names persist. The town of Kilifi is believed to originate from the Swahili word Mkilifi, referring to the neem tree (Azadirachta indica), a medicinal and shade-giving species that thrives in the coastal climate. The neem’s bitter leaves and healing properties made it a household remedy, and its name became part of the identity of the region.

These examples show how trees once defined not only our environment but also our sense of place and belonging. When you think of it, each name; Kagumo, Kamiti, Kileleshwa, Muthaiga, Karatina, Kilifi, is a story carved in language, a piece of natural history that still breathes through everyday speech.

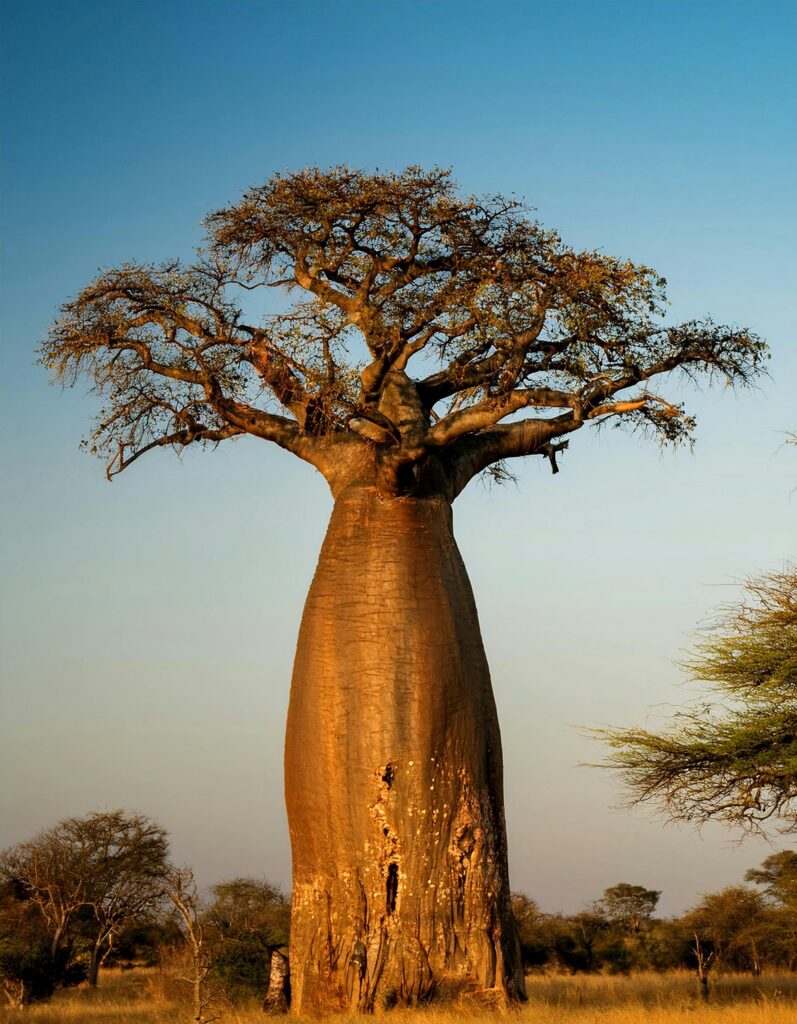

Across East Africa, this pattern repeats. In Tanzania, places like Mbuyuni literally mean “place of the baobab tree.” The baobab; massive, majestic, and life-giving, stores water in its trunk, feeds both people and animals, and shelters birds and bats. It’s no wonder that entire communities identified themselves by proximity to this living monument.

Place names derived from trees are not coincidences. They are testimonies. They tell us what people valued, what they saw when they first settled, and what the land once offered. Each name is a reminder that our culture is rooted, quite literally, in nature.

As Kenya grows and urbanizes, many of these trees have vanished, replaced by glass towers, tarmac, and neon lights. But their memory remains in our words. Every time we say “I live in Kileleshwa” or “I’m from Karatina,” we echo the names of trees our ancestors once sat beneath.

Perhaps the trees are gone, but their roots still live in our tongues, our stories, and our maps. And if we listen closely, we might just hear the whisper of their leaves in the names we speak every day.

About the Author:

David Wakogy is a historian and environmentalist with a passion for uncovering the deep connections between nature and human culture. He can be reached at dwakogy@gmail.com.