Contact : +254 725 877 146

I Killed a Monkey: International Primate Day

Promoting sustainable financing and community engagement is key to effective primate conservation.

International Primate Day is observed every year on September 1st. This year, it stood as more than a date on a calendar; it was a global call to protect our closest relatives in the animal kingdom. Nowhere was this call more critical than in Africa, home to iconic yet endangered species like the mountain gorilla and the chimpanzee. For me, this day always resonated with a profound personal journey, a complete transformation from seeing primates as pests to understanding them as irreplaceable beings worthy of our utmost respect and protection.

My early perspective wasn’t one of awe. As a child growing up at the edges of R. Nzoia, I saw monkeys as enemies. They were invaders, a threat to our family’s livelihood. I vividly recalled one afternoon when a troop of vervet monkeys had invaded our maize farm. What began as a game quickly escalated. My friends and I ganged up on one individual, chasing it for hours, our shouts echoing through the field as we threw stones. It was a protracted, distressing struggle, and when we finally ended its life, we threw its body into the River Nzoia. Back then, it felt like a victory, a defense of our crops. Years later, that memory filled me with a deep sense of regret. It was a moment of ignorance, a failure to see the creature as anything more than a nuisance.

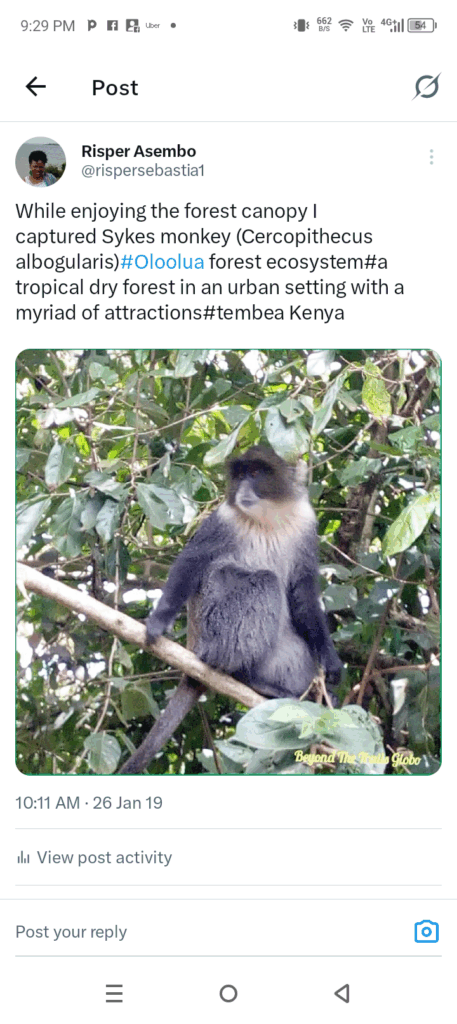

That regret became the fuel for my education. Enrolling in Wildlife Management and Conservation studies opened my eyes to a new reality. I learned about the intricate balance of ecosystems and the vital roles each species played. But it was my practical stay at the Kenya Institute of Primate Research from 2017 to 2019 that truly revolutionized my understanding. There, I was granted the privilege of interacting intimately with non-human primates, primarily the Olive baboons (Papio anubis) and the Sykes monkeys (Cercopithecus albogularis).

My duties involved taking care of the olive baboons, which included meticulous health monitoring. I was tasked with reading their menstrual cycles, and at first, I was utterly shocked. The cycle was remarkably similar to that of a female human being. This biological kinship was the very reason they are so valuable in ethical biomedical research; they are our mirrors in the natural world. This wasn’t just data; it was a profound connection that dismantled my old prejudices.

In 2018, my growing passion for primatology led me to an extraordinary opportunity: attending the International Primatological Society Congress at the United Nations in Nairobi. There, I learned a great deal about primates of the world from researchers representing diverse countries across the globe. This global perspective deepened my appreciation for the interconnectedness of primate conservation efforts worldwide and reinforced the importance of international collaboration in protecting our closest animal relatives.

Beyond the research enclosures was the Oloolua Forest ecosystem. Walking through its dense canopy was a daily privilege. No day passed without the chattering arrival of a troop of Sykes monkeys. Sometimes they came in larger groups of about 50 individuals, moving through the trees with an effortless grace. Their intelligence and complex social bonds were undeniable. They were curious and mischievous; on some days, if we left the office door open, they would venture in, their quick eyes scanning for an opportunity to snatch food. These were not pests; they were personalities.

This hands-on experience illuminated a larger, global truth: primates are intelligent, social, and emotionally complex. Sharing up to 98% of our DNA, observing them felt like looking into a mirror of our own evolutionary past. Beyond their intrinsic value, they are keystone species. As seed dispersers, they are master forest gardeners, helping regenerate the very ecosystems that provide us with clean air, water, and stability. Protecting primates means protecting entire habitats.

Yet, their situation is precarious. Statistically, there are over 540 primate species worldwide. Kenya is blessed to host 20 of them. Yet, globally, according to the IUCN, a staggering number of species are classified as Critically Endangered. Alarmingly, four (4) of these severely threatened species are found within Kenya’s borders. They face a barrage of threats: habitat loss from logging and farming, the illegal bushmeat trade, disease transmission from humans, and the overarching disruption of climate change. Without urgent action, we risk losing them forever.

My personal journey from a participant in killing to an educator and advocate is living proof that change is possible. Armed with knowledge and experience from both local research and global conferences, I returned to my community. I spoke with them about the ecological role of primates, explaining how they were not just thieves of crops but essential gardeners of the forests that sustained our environment. We discussed humane deterrents and coexistence strategies. Slowly, attitudes began to shift. We were learning to share the landscape.

This International Primate Day, I remembered that transformation. The day served as a reminder that our fates are intertwined. We have the power to be their greatest threat or their most dedicated guardians. The call to action is clear: we can choose to be responsible travelers, supporting ethical tourism that funds conservation. We can choose to support primate sanctuaries and research organizations working on the front lines. We can choose to educate ourselves and others, spreading awareness and fostering coexistence. Let us choose to be guardians. Let us choose a future where primates not only survive but thrive, forever wild and free in the ancient forests they call home